In the dense, mist-shrouded forests of Leyte, Ed Permangil spent three decades mastering the art of the hunt. As a young man, hunger drove him to set crude yet effective snare traps deep in the jungle. “Whenever I had no money for food, I used to set traps like this,” he explains, demonstrating how a spring-loaded device could entangle a pig’s leg, leaving it helpless for days. “Snared pigs can last up to a week before dying of dehydration. We slaughter, gut, and chop them right in the jungle—bringing down only the meat.”

Ed was one of countless baboy damo (wild pig) hunters who relied on this trade, selling lean, gamey pork for as much as PHP700 per kilo. Over the years, he estimates that he has caught nearly a thousand wild pigs.

But Ed’s story is not just one of survival—it is also a tale of transformation.

A Vanishing Icon of the Philippine Wilderness

The Philippines is home to five species of wild pigs, all of which are now in danger of extinction:

Philippine Warty Pig (Sus philippensis) – Vulnerable

Oliver’s Warty Pig (S. oliveri) – Vulnerable

Palawan Bearded Pig (S. ahoenobarbus) – Near Threatened

Visayan Warty Pig (S. cebifrons) – Critically Endangered

Bearded Pig (S. barbatus) – Vulnerable (found in Tawi-Tawi, as well as Indonesia and Malaysia)

Centuries of hunting, deforestation, and hybridization with domestic pigs have devastated their numbers. One of the biggest threats? The illegal bushmeat trade, which still thrives in parts of the country.

Snuffling for snacks. Wild pigs have a highly developed sense of smell and can find food buried deep beneath the soil. A pig’s sense of smell is over 2000 better than ours.

“Ping Pong” Pig Bombs and Other Hunting Methods

While some hunters, like Ed, relied on traditional traps, others turned to more gruesome methods. Iñigo Orias, a former hunter, once preferred using explosives. “This is a type of pig-killing bomb called a pong because it looks like a ping-pong ball,” he says, showing off three gleaming silver spheres.

Each pong contained a deadly mixture of gunpowder, match heads, and ceramic shrapnel, all dipped in wax for waterproofing. Hunters would wrap the explosives in rotting bait, such as water buffalo hide, and wait for an unsuspecting pig to take a bite. “When the pig bites, the primer ignites—and its head explodes.”

For many hunters, the risk of being mistaken for rebel combatants by the military made carrying firearms dangerous. This led to a rise in passive hunting methods like snares, poisoned bait, and explosives—all of which continue to harm the country’s fragile ecosystems.

Philippine Warty Pig (Sus philippensis) at a holding facility in Luzon. Hunted for thousands of years and now classified by the IUCN as Vulnerable, it has become so rare that when an old boar was spotted on Mt. Apo in April 2022, it made headlines. This young male has yet to grow distinctive tusks and facial hair. (

The Philippine Warty Pig (Sus philippensis) is the most widely distributed of the country’s five wild pig species. Sporting stylish mohawks, nifty bangs, cool beards and facial warts, ‘Baboy Damo’ have been pushed deep into the country’s forests due to a combination of hunting, habitat loss and diseases such as African Swine Fever. Accidental crossbreeding with domestic pigs is also a major threat.

The Law vs. The Hunt: Can We Save the Baboy Damo?

Under Republic Act No. 9147, also known as the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, hunting native wildlife is strictly prohibited. “Anyone found guilty of killing a threatened species may face fines of PHP20,000 to PHP1,000,000 and/or one to 12 years in jail,” explains wildlife researcher Emerson Sy.

Despite these laws, illegal hunting persists, fueled by high demand for wild meat. Baboy damo is still openly sold in some online forums, despite crackdowns by authorities.

From Hunters to Guardians of the Forest

The story of Ed Permangil and Iñigo Orias, however, takes a hopeful turn.

In 2019, Ed hung up his traps and became a Barangay Forest Protection Brigade patrolman under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). His mission? To stop others from making the same mistakes he did.

Similarly, Iñigo now works to educate communities about the importance of conservation. “I spent years hunting these pigs,” he admits. “Now, I spend my days trying to protect them.”

A New Hope for the Baboy Damo

Efforts to save the Philippine Warty Pig are gaining momentum. Organizations like the Energy Development Corporation (EDC) have included the species in their BINHI Flagship Species Initiative (FSI), alongside other endangered creatures like the Visayan Hornbill and the Giant Golden-Crowned Flying Fox.

“Wild pigs play a critical role in our ecosystems,” says Atty. Theresa Tenazas, former DENR Wildlife Resources Division Chief. “They help regenerate forests by aerating the soil and dispersing seeds. Instead of seeing them as pests, we need to recognize their value.”

Nelmar Aguilar, EDC’s Watershed Management Officer for Leyte, agrees: “Beyond sustainable development, we need regenerative development—a way to protect not just the environment, but also the people who depend on it.”

Hogtied. Snare traps allow hunters to catch and transport live pigs. “Since it’s hard and dangerous to carry a struggling pig, we usually kill, gut and chop it up onsite, keeping only the meat,” reveals a former trapper.

The Battle Continues

The Philippine Warty Pig is fighting for its survival against illegal hunting, habitat destruction, and hybridization. The question remains: Will we act fast enough to save it?

With former hunters like Ed and Iñigo now on the frontlines of conservation, there is hope. But laws must be enforced, awareness must spread, and the demand for bushmeat must end.

Only then can we ensure that future generations will still hear the calls of the baboy damo echoing through the Philippine forests.

What Can You Do?

Report illegal wildlife hunting and trade to the DENR.

Support organizations working to protect the Philippine Warty Pig.

Raise awareness about the importance of conserving our native wildlife.

The fate of the baboy damo—and our forests—rests in our hands.

Contributed by Gregg Yan

.JPG)

.jpg)

%20(26).jpg)

.jpg)

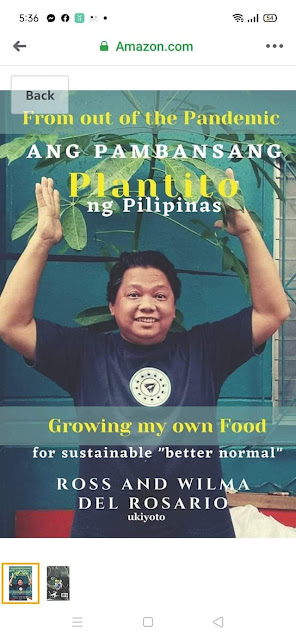

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.