Wazzup Pilipinas!?

The Philippines is a fascinating anomaly in the history of Spanish colonization. While most former Spanish colonies, particularly in Latin America, retained Spanish as their primary language, the Philippines, despite 333 years of Spanish rule, did not. Instead, the country developed its own linguistic tapestry, heavily influenced by Spanish but predominantly reliant on its native languages and, later, English. Why did this happen? Let’s unravel the unique circumstances behind this linguistic divergence.

The Complexity of Language in a Diverse Archipelago

The Philippines, an archipelago with over 7,000 islands, is home to more than 175 languages and dialects. When Spanish missionaries arrived in the 16th century, they were faced with a daunting challenge: how to evangelize a population so linguistically diverse. Unlike Latin America, where indigenous populations were often replaced or assimilated by European settlers, the Philippines’ geographic isolation preserved its regional dialects.

Instead of imposing Spanish on the entire population, missionaries learned the major local languages like Tagalog, Cebuano, and Ilocano to spread Christianity. This practical decision allowed them to communicate effectively but limited the spread of Spanish to the elite and clergy. In contrast, in Latin America, the Spanish language became a unifying force among diverse indigenous groups.

Spanish as the Language of the Elite

Spanish in the Philippines was primarily reserved for the illustrados (educated elite), mestizos, and clergy. It became the language of governance, religion, and trade. For the majority of Filipinos, however, daily life revolved around their native dialects. While many Filipinos understood basic Spanish terms due to its integration into public life, fluency was rare outside of the upper classes.

Evidence of Spanish influence is still visible today. Many Filipino words, public documents, land titles, and legal terminologies from the Spanish era remain in use. Words like mesa (table), silla (chair), and barrio (village) are just a few of the thousands of loanwords that have been absorbed into Filipino languages.

The Role of American Colonization

The decline of Spanish in the Philippines can largely be attributed to American colonization after the Spanish-American War in 1898. The Americans implemented a new education system, making English the medium of instruction and the official language of governance. This swift shift marginalized Spanish, which was already limited to a fraction of the population.

By the mid-20th century, English had become the dominant second language of Filipinos, relegating Spanish to historical and ceremonial contexts. However, it’s worth noting that Spanish remained in public documents and education for several decades, with its presence dwindling only by the 1950s.

Chavacano: A Lingering Legacy

One of the most intriguing remnants of Spanish influence in the Philippines is Chavacano, a Spanish-based creole spoken in parts of Zamboanga, Cavite, and Ternate. Chavacano mixes Spanish vocabulary with Filipino grammatical structures, creating a unique linguistic hybrid. Though not identical to standard Spanish, it stands as a testament to the enduring impact of Spanish colonization.

Comparisons to Latin America

The Philippines’ linguistic journey contrasts sharply with that of Latin America. In countries like Mexico, Colombia, and Peru, Spanish became the dominant language due to extensive European settlement and the displacement or assimilation of indigenous populations. Missionaries in Latin America spread Christianity alongside Spanish, creating a more unified linguistic landscape.

In the Philippines, however, Spanish colonizers were a small ruling class, and the focus remained on religious conversion rather than linguistic unification. Additionally, the archipelago's strategic importance lay in its trade routes rather than its natural resources, further reducing the incentive for Spain to invest in widespread Spanish education.

A Cultural Victory

The resistance to adopting Spanish as a national language can also be seen as a form of cultural resilience. By retaining their native dialects, Filipinos preserved a sense of identity amidst centuries of colonization. This linguistic diversity remains a source of pride and a marker of the country’s rich heritage.

The Modern Perspective

Today, the Philippines is one of the most linguistically diverse nations in the world, with English serving as a lingua franca and Filipino (based on Tagalog) as the national language. Spanish has faded into history for most Filipinos, but its legacy endures in the country’s vocabulary, traditions, and even surnames.

Filipinos have embraced their linguistic diversity as a strength, a testament to their adaptability and resilience. The story of why the Philippines doesn’t speak Spanish is not just about history—it’s about identity, culture, and the enduring spirit of a people who have carved their own path through the complexities of colonization and globalization.

In the words of a modern observer, “The failure of Spain to propagate Spanish is a form of resistance and cultural victory for Filipinos.”

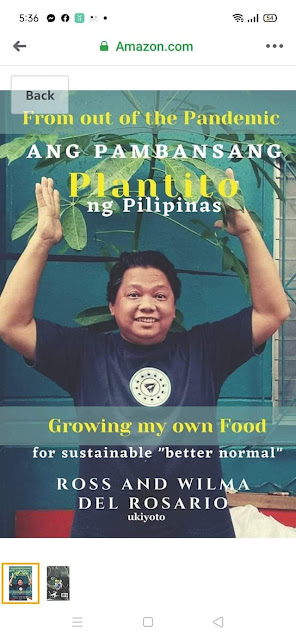

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.