Wazzup Pilipinas!?

I’m surrounded by mutant fish inside Lake Malawi in South Africa.

Like Spiderman, Wolverine and Magneto, they’ve developed different abilities: most evolved to graze on algae, which coats the enormous boulders around us. Others snuffle through the sand for worms and other wriggly tidbits. Some play dead and suddenly turn the tables on their hapless prey, while others rip and eat the scales off unsuspecting neighbors.

I glance at my dive guide, Felix Sinosi, while fiddling with my GoPro. I hope the tiny camera captures the swirling melee of color around us: neon blues and brilliant tangerines, glimmering stripes, speckles and spots. The fish patterns were so mesmerizing I almost forgot the warning Felix shared right before we back-rolled into the lake’s blue waters: “A large Nile crocodile was spotted swimming here yesterday.”

Cichlids of Lake Malawi

Meet the mbuna (em-buna), Lake Malawi’s mutant fish. They’re cichlids (sick-lids), members of a large family of freshwater fish whose members range from the striped angelfish of the Amazon Basin to the tasty tilapia we farm and eat in the Philippines.

I’m a Pinoy SCUBA diver and I travelled 10,000 kilometers to see these fish – some of which I’ve kept in my bubbling aquarium at home – in their home surf.

There are 1500 known cichlid species and over 600 of them inhabit just one lake, where fish mutate into new species every few thousand years. Scientists postulate that Lake Malawi’s 600 cichlid species evolved from a handful of fish that entered the lake three million years ago. These ‘ancestor fish’ showed an unusually high level of genetic mutation and when they started colonizing Lake Malawi, their mutant genes spurred an intense period of speciation.

Earth’s Most Biologically-Diverse Lake

A 2018 paper by Malinsky et al. observes how “The formation of every new lake or island represents a fresh opportunity for colonization, proliferation and the diversification of living forms. In some cases, the ecological opportunities presented by underutilized habitats facilitate what scientists call adaptive radiation – rapid and extensive diversification of the descendants of the colonizing lineages.”

The first to observe this was no less than Dr. Charles Darwin, who noticed that in the Galapagos Islands, tiny birds called finches morphed into different species to fill various ecological niches. So too did the tiny cichlids evolve to colonize their giant new lake.

Lake Malawi slices through the South African nations of Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania. From afar, it looks like the ocean. Over 580 kilometers long and up to 700 meters deep, the lake’s so vast that flying from end-to-end is like flying from Manila to Cebu.

In 1984, all of Lake Malawi was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its incredible scientific value as a hotbed for fish evolution. Its fish are generally divided into two types: mbuna are rock-dwelling cichlids, while utaka (ooh-taka) are open water cichlids which either feed on drifting plankton or each other.

Interesting behavior plus vivid coloration have endeared these mutant fish to the world’s aquarists, who have been keeping and breeding them since the late 1950s. Melanochromis auratus, Pseudotropheus elongatus, Maylandia zebra and many others are mainstays of the ornamental fish industry.

“The colors of mbuna are brilliant enough that they can be confused for coral reef fish,” notes Pinoy cichlid hobbyist Angel Ampil, who has been keeping fish for over 50 years. “Mbuna have distinct courtship and breeding behavior, plus they are relatively easy to breed in captivity.”

Malawi’s cichlids are probably the country’s best ambassadors. “The tropical aquarium trade has sent our cichlids all over the world,” explains Dr. Harold Sungani, Deputy Director of the Monkey Bay Fisheries Research Centre. “In addition to generating vital revenue which can be channeled back into conservation and sound fisheries management, our cichlids continuously generate interest for tourists to visit Malawi and see the fish in the wild. Tourism in turn, spurs peripheral trades like woodcarving and handicraft painting. The people of Malawi can see the importance of conserving a lake which brings business to local communities.”

However, not all is well in Lake Malawi, which is beset by the challenges of overpopulation and a changing climate.

Threatened by Climate Change and Overfishing

The population of Malawi, among the world’s poorest nations, is growing steadily. In the 1960s the country hosted less than four million people. Today there are over 20 million, around half of which live below the poverty line.

As a largely agrarian nation, one of Malawi’s lifelines is its lake, which produces up to 60% of the country’s protein in the form of both fresh and dried fish. Visiting several markets from the capital of Lilongwe to the southern tip of the lake in Mangochi, I saw heaps of dried utaka and usipa, open water cichlids and sardines which sell for as little as USD1 (PHP55) per bucket.

Inexpensive and readily available, these small fish constitute one of the country’s prime commodities, with Malawians consuming an average of 8.1 kilogrammes of fish yearly.

But overfishing is threatening the lake’s productivity. Decades of it has greatly reduced the lake’s food fish, with many fishers returning to shore with just one or two bucketfuls – barely enough to cover the cost of fuel.

“Malawi’s rapidly growing population is exerting enormous pressure on our country’s natural resources, particularly small fish like usipa (freshwater sardines) and kambuzi (shallow water cichlids),” adds Dr. Sungani. “Curbing population growth is a good way to ease pressure on Lake Malawi.”

Climate change is another serious challenge. Since the year 2000, parts of Africa have been seeing less and less rainfall, causing massive droughts in nations like Somalia and Ethiopia. Malawi is relatively lucky, but the water level of its largest lake has dropped around three meters since the 1980s.

The introduction of invasive species also looms large. In Africa’s largest lake, Lake Victoria, the introduction of Nile Perch (Lates niloticus) has proven disastrous. In an attempt to boost fisheries productivity, the predatory fish were introduced to the lake in the 1950s. Growing over two meters, they soon preyed on over 100 other fish species, practically wiping out 60% of the lake’s native cichlids in what may be the largest vertebrate extinction of the 20th century.

“What we need is sensible management to ensure that these special fish sustain both local communities and ecotourism for many years to come,” says Dr. Sungani.

Back in the lake, visibility has gone bonkers. I’m following a family of golden Auratus cichlids when I hear the metallic tink, tink, tink of someone banging on his tank. Is the Nile crocodile back for a buffet? Has a curious hippo left the shallows to check us out? A large, dark shadow appears. I stop dead in the water.

In seconds it morphs – mutates if you will – into the form of Felix, signaling us to move on. Exhaling in relief, I follow him to see what scaly wonders lie over the next patch of rocks, recalling what I read before going to Africa.

“By learning how Malawi’s cichlids adapt and evolve under selective pressure, we can learn how these pressures affect humans in terms of health and disease,” remarked Federica Di Palma, Science Director at The Genome Analysis Centre in the United Kingdom and co-author of a 2014 Harvard and MIT study on adaptive radiation.

With COVID-19 mutating every few months and losses amounting to trillions of dollars and millions of souls, it might just pay dividends for us to keep studying the mutant fish of Lake Malawi.

CAPTIONED IMAGES:

Pinoy explorer Gregg Yan and SCUBA guide Felix Sinosi from Cape Maclear before jumping into Thumbi Island. Beneath the boat are spotted-necked otters (Hydrictis maculicollis), which submerged moments before the image was taken.

Lake Malawi lies in Malawi, a landlocked nation in southeastern Africa. Home to Nile crocodiles, hippos and fish, the lake hosts the world’s highest concentration of fish species in a single lake. Mufasa Eco Lodge is one of the best places to launch your expeditions.

Shallow water dives and shore entries are easily conducted, owing to the lake’s gentle currents. Pinoy explorer Gregg Yan and Malawi dive master Felix Sinosi check their equipment before documenting freshwater habitats in Thumbi Island.

Auratus cichlids (Melanochromis auratus) display striking patterns and bold behavior at Masasa Reef. Among the first mbuna or rock-dwelling cichlids to be kept in captivity, these belligerent fish were first exported from Lake Malawi in 1958 and have since been bred across the globe.

An elongate cichlid (Pseudotropheus elongatus) gleams like a striped sapphire in Thumbi Island, Malawi. Lake Malawi is home to over 600 cichlid species (plus thousands of color morphs), with more being discovered yearly. The lake hosts well over 1000 species of fish, more than any other lake on Earth.

This zebra mbuna (Maylandia zebra) sticks out like a sore thumb amidst the drab hues of the lake. Cichlids are evolutionary marvels – intelligent and dedicated fish who often rear their young inside their mouths in a parental strategy called mouthbrooding.

Brightly colored fish. Hardy and fast-growing mbuna at a display tank in the Philippines. “Malawi’s cichlids are probably our country’s best ambassadors. The tropical aquarium trade has sent our cichlids all over the world,” says Dr. Harold Sungani, Deputy Director of the Monkey Bay Fisheries Research Centre in Malawi.

A swirl of color. Malawi Rift Lake cichlids are among the world’s most popular freshwater aquarium fish. They can be kept in dense concentrations with strong filtration. Shown is a Malawi-themed tank in the Philippines. “Hobbyists should avoid cross-breeding cichlid species to keep genetic lines pure,” says Pinoy cichlid hobbyist Angel Ampil. A similar Rift Lake north of Malawi, Lake Tanganyika, hosts about 250 endemic cichlid species.

Mbuna or rock fish in their natural habitat, algae-coated rocks called aufwuchs (German for algae and surface growth) in brightly-lit areas of the lake. These fish were aggregating in less than two meters around the shallow portions of Cape Maclear.

Insect tornadoes. Billions-strong swarms of nkungo (en-kunggo) or lake flies (Chaoborus edulis) form tornado-like plumes that stretched hundreds of feet tall. When these flies come ashore, they’re harvested with nets and fried into burger patties.

Usipa or freshwater lake sardines (Engraulicypris sardella) drying at a roadside in Mangochi, Malawi. Washed in scalding water and deep-fried in batter, the fish provide vital protein for Malawi’s growing population. According to World Fish, fish accounts for 60% of the country’s protein, with the average Malawian consuming 8.1 kilogrammes of fish early.

Aquatic plants feature heavily in the shallow waters of Lake Malawi, something not usually seen in the bare rocky tanks which constitute Malawi-themed aquaria. Malawi’s colorful biotopes can be seen here.

Lake Malawi National Park: World Heritage Site served as an excellent resource for identifying potential dive sites and the many colorful cichlids we saw over the course of a week. It was written by Dr. Kenneth R. McKaye and is available on Amazon.

Captive bred cichlids. Though a few thousand fish are still annually caught for the ornamental fish trade, the great majority of Malawi’s fish have been bred commercially for decades. Shown are three types of yellow mbuna bred and raised in the Philippines.

Malawi is known as the ‘Warm Heart of Africa’ due to the genuine friendliness of its people, many of which hail from its great tribes including the Chewa, Nyanja, Lomwe and the Zulu or Nguni. Shown is Pinoy explorer Gregg Yan with three Zulu tribesmen who just conducted a ritual arm scarring ceremony.

.jpg)

.jpg)

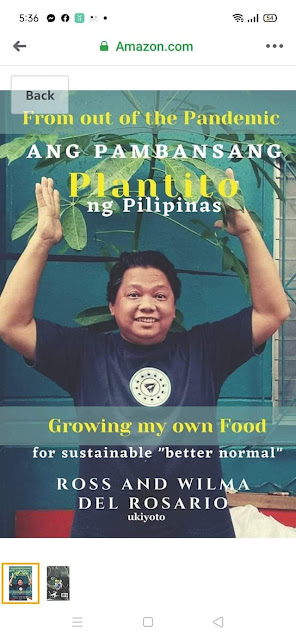

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.